Research Rabbit Hole – Could You Contact Someone on a Moving Train in 1939?

In Book #3 in the Viv & Charlie Mystery Series, I had to have a way for a person to be able to contact another person while that second person is on a train traveling cross country. Was that even possible in 1939? The answer, surprisingly, is yes.

Telegraphy was a completely wire-dependent method of communication (just like telephones were once upon a time). Wires were strung from telegraph office to telegraph office. Those wires carried the signals that were then translated into words on telegrams. No wire, no office/telegraph operator = no telegram. Ah, but train stations did have telegraph offices. In 1939, you could send a telegram to a train station and have that telegram delivered to a person on a train that stopped at that station as it was making its way cross country. But in order to do that, you not only needed the name and number of the train, the direction of travel, the stop, the time the train stopped at that station, but also the name, and car number of the person traveling that you wanted to reach. Logistically sticky, but possible, yes, and possible is all I need to include in the story.

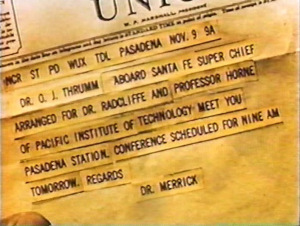

This a still of a telegram being delivered to a passenger on the famous Santa Fe Super Chief from the 1954 movie, 3 for Bedroom C. (The Super Chief is in my Book #3!)

Most people these days associate telegrams with tragedy – since the only way we’ve seen them represented is in war movies where they have the scene of the mother receiving news of her son’s death by special delivery telegram.

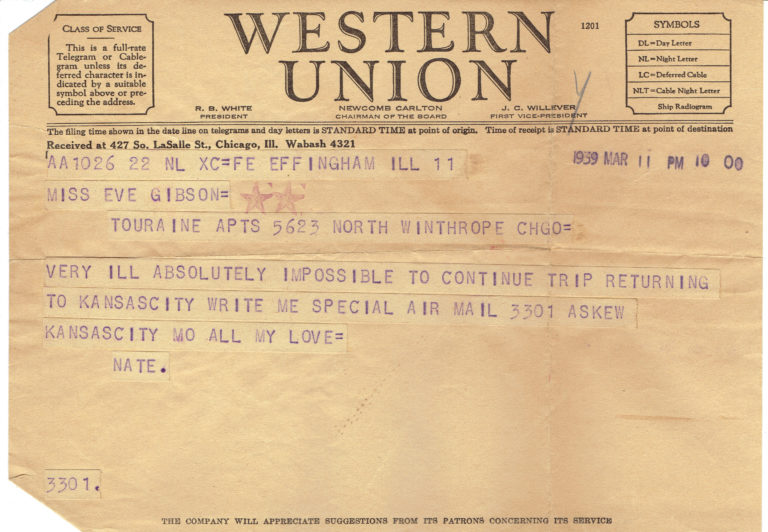

But before WWII, telegrams were commonly used for any cheap long distance communication (good, bad, and neutral news included). Long distance telephone service existed then, but it was crazy expensive. In 1950, a 5-minute call between New York and LA cost $3.70 (That’s $38.07 in 2017 dollars!)

Western Union was the most popular company and they charged the sender by the word, so writing a telegram was an art unto itself. Here’s a whole Telegram writing guideline from 1928 if you really want to get into the weeds.

And here’s an extra video of a telegram delivery man doing tricks on his route just for fun. Enjoy.